VM-based obfuscation in Rhadamanthys Stealer

Overview

Rhadamanthys is an infostealer that has recently been spreading through malicious Google ads. The program decrypts several layers of shellcode before retrieving the second stage of its payload from its C2 server. This writeup provides an excellent explanation of the process, but I wanted to look more closely at the obfuscation methods used to hide the shellcode.

The sample I used in this writeup is available at MalwareBazaar here.

The Virtual Machine

Looking at the strings in the sample, I immediately noticed a very long string beginning with 7ARQAAAASCI. This string appears in every sample of Rhadamanthys I’ve seen so far.

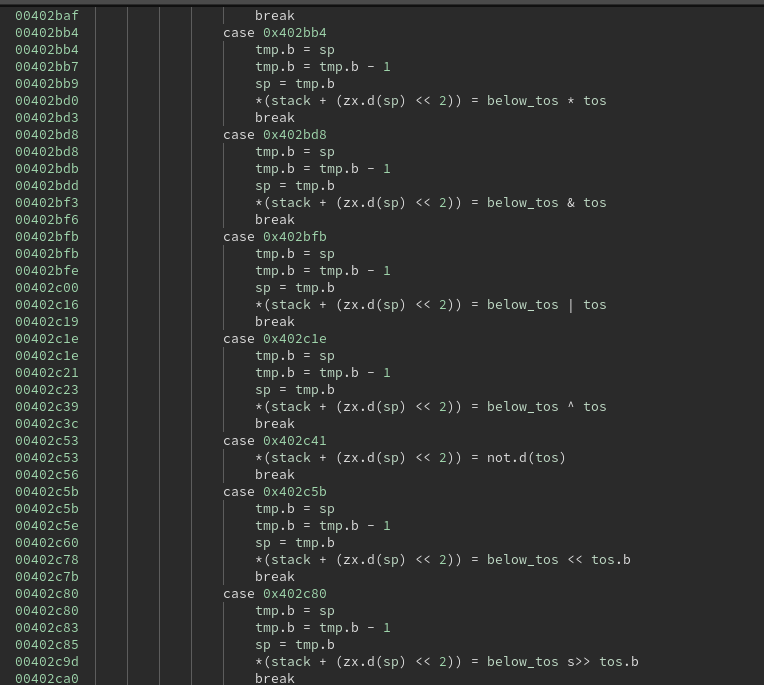

Since the string contained only numbers and uppercase letters, I suspected that base32 was being used, but my attempts to decode the string as base32 failed. In the process of looking for a decryption function, I found what appeared to be operations associated with a virtual machine:

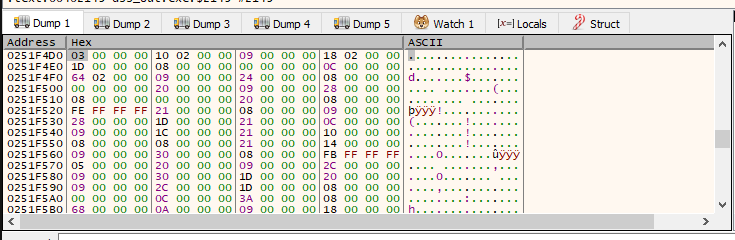

Upon closer inspection, I found what appeared to be the opcodes of the virtual machine in memory when this function was called, at an offset of 0xc from the first argument. Each of the opcodes is stored as a value from 0 to 52, sometimes followed by a single operand in the form of a 32-bit integer.

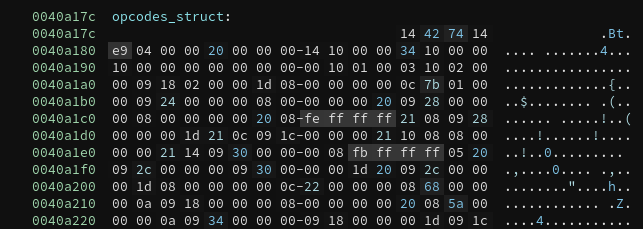

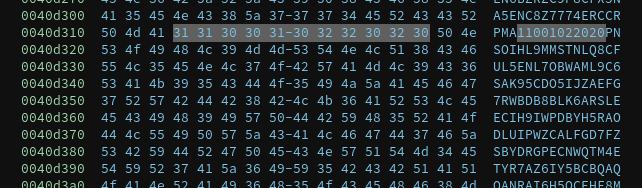

The opcodes are also hard-coded in the memory of the program:

Writing a Disassembler

From Opcodes to Addresses

I found that there was a layer of obfuscation designed to obscure which opcodes corresponded to which operations. The program stores a table of 53 values:

[4203120, 4203138, 4203140, 4204027, 4204069, 4203673, 4204001, 4204014, 4203142, 4203215, 4204161, 4204224, 4204275, 4204326, 4204377, 4204428, 4204479, 4204530, 4204581, 4204632, 4204683, 4204734, 4204814, 4204894, 4204974, 4205054, 4205134, 4203405, 4203349, 4203294, 4203531, 4203495, 4203461, 4203565, 4203621, 4205770, 4205802, 4205214, 4205240, 4205275, 4205310, 4205346, 4205383, 4205419, 4205456, 4205492, 4205528, 4205563, 4205598, 4205633, 4205659, 4205696, 4205733]

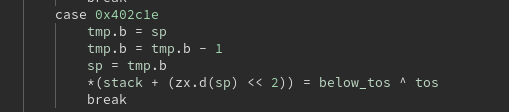

When an instruction is run, the program retrieves the value at the index of the corresponding opcode. Then, a long switch statement compares this value to the index of possible values for each instruction.

For instance, the XOR instruction corresponds to a value of 0x402c1e, which is at index 48 of the array. Therefore the opcode for XOR is 48.

Reversing the Instruction Set

There are 52 different instructions, though some of them appear to be duplicates. There were a few instructions I wasn’t able to figure out (especially the ones related to manipulation of floating-point values). These are marked with a ? in the disassembly script below. If I have time later, I may go back and figure out what these instructions are.

The virtual machine is stack-based, with most operations acting on the top of the stack and the value directly below it. We have the option to push immediate values (push_imm) or values at a memory address relative to a given offset (push_indirect).

Some of the opcodes call other functions in the program. Most importantly, the instruction I refer to as get string in the disassembly retrieves a sequence of bytes from the long, seemingly base32-encoded string I mentioned earlier.

The script I used to disassemble the instructions is given below:

import binascii

op_dict = {0: 4203120, 1: 4203138, 2: 4203140, 3: 4204027, 4: 4204069, 5: 4203673, 6: 4204001, 7: 4204014, 8: 4203142, 9: 4203215, 10: 4204161, 11: 4204224, 12: 4204275, 13: 4204326, 14: 4204377, 15: 4204428, 16: 4204479, 17: 4204530, 18: 4204581, 19: 4204632, 20: 4204683, 21: 4204734, 22: 4204814, 23: 4204894, 24: 4204974, 25: 4205054, 26: 4205134, 27: 4203405, 28: 4203349, 29: 4203294, 30: 4203531, 31: 4203495, 32: 4203461, 33: 4203565, 34: 4203621, 35: 4205770, 36: 4205802, 37: 4205214, 38: 4205240, 39: 4205275, 40: 4205310, 41: 4205346, 42: 4205383, 43: 4205419, 44: 4205456, 45: 4205492, 46: 4205528, 47: 4205563, 48: 4205598, 49: 4205633, 50: 4205659, 51: 4205696, 52: 4205733}

has_operand = [4203142, 4203215, 4203565, 4203621, 4206427, 4204224, 4204275, 4204326, 4204377, 4204428, 4204479, 4204530, 4204581, 4204632, 4204683, 4204734, 4204814, 4204894, 4204974, 4205054, 4205134, 4204069, 4204027]

insn_names = {4203120: 'halt', 4203140: 'nop', 4203142: 'push_imm', 4203215: 'push_indirect', 4203294: 'load', 4203349: 'load', 4203405: 'load', 4203495: 'pop word', 4203461: 'pop dword', 4203531: 'pop byte', 4203565: 'pop_indirect', 4204101: 'call sub_402e1d', 4203673: 'get string', 4204001: '?', 4204014: 'pop', 4204027: '?', 4204069: '?', 4204161: '?', 4204224: 'jeq', 4204275: 'jne', 4204326: 'jl', 4204377: 'jle', 4204428: 'jg', 4204479: 'jge', 4204530: 'jl', 4204581: 'jle', 4204632: 'jg', 4204683: 'jge', 4204734: 'jne? [float]', 4204814: 'je? [float]', 4204894: 'jae? [float]', 4204974: 'ja? [float]', 2107902: 'jbe? [float]', 4205134: 'jb? [float]', 4205214: 'not', 4205240: 'add', 4205275: 'sub', 4205310: 'divs', 4205346: 'divu', 4205383: 'mods', 4205419: 'modu', 4205456: 'mul', 4205492: 'mul', 4205528: 'and', 4205563: 'or', 4205598: 'xor', 4205633: 'not', 4205659: 'shl', 4205696: 'asr', 4205733: 'lsr', 4205770: '?', 4205802: '?'}

def get_op_name(n):

return insn_names[op_dict[n]]

insns_hex = open('ops_hexdump.txt').read().replace(' ','')

insns = []

full_str = ''

has_operand_flag = False

for i in range(0, len(insns_hex), 8):

insn_str = insns_hex[i:i+8]

insn = int.from_bytes(binascii.unhexlify(insn_str), 'little')

if(has_operand_flag):

full_str += hex(int.from_bytes(binascii.unhexlify(insn_str), 'little'))

print(full_str)

full_str = ''

has_operand_flag = False

else:

try:

addr = op_dict[insn]

if addr in has_operand:

has_operand_flag = True

full_str += hex(i // 8) + ' ' + get_op_name(insn) + ' '

else:

full_str += hex(i // 8) + ' ' + get_op_name(insn) + ' '

print(full_str)

full_str = ''

except:

pass

print('bad', insn_str)

The Obfuscated Functions

Constructing Strings

Looking at the disassembly, we can see the program construct several interesting strings. This sequence of instructions loads the string kernel32.dll into memory:

0x26b push_indirect 0x18

0x26d push_imm 0x6b

0x26f pop byte

0x270 push_indirect 0x19

0x272 push_imm 0x65

0x274 pop byte

0x275 push_indirect 0x1a

0x277 push_imm 0x72

0x279 pop byte

...

Later on, the same process is used to build the strings 41 ? 76 ? 61 ? 73 ? 74 and 73 ? 6E ? 78 ? 68 ? 6B. The hexadecimal values in these strings spell out Avast and snxhk respectively. Some googling reveals that snxhk is the name of a DLL associated with Avast antivirus. Presumably this means that the program is attempting to evade antivirus, but so far I haven’t looked into the specifics of how it does so.

Base32 Decryption

Eventually, I managed to find something that looked like base32 decryption. This comparison loads a character and checks whether it is between A and Z:

0x624 load

0x625 push_imm 0x41

0x627 jl 0x639

0x629 push_indirect 0xc

0x62b load

0x62c push_imm 0x5a

0x62e jg 0x639

And this comparison checks for a character between 4 and 9:

0x641 load

0x642 push_imm 0x34

0x644 jl 0x659

0x646 push_indirect 0x10

0x648 load

0x649 push_imm 0x39

0x64b jg 0x659

This explains why attempting to decode the base32 earlier failed: the program is using the alphabet [A-Z][4-9], rather than the more conventional [A-Z][2-7].

There’s still one more step we have to go through before we can decode the long string. The long string contains several sequences of the characters 0, 1, and 2, which aren’t part of the base32 character set that’s being used here.

It may be that these sequences are being used to encode information in a different way, but it’s entirely possible that they’re just there to make it harder to identify the alphabet being used for the base32 encoding. I replaced them all with the character A before decoding.

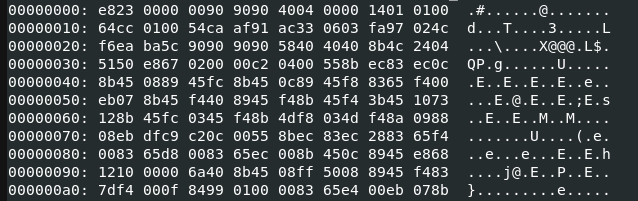

At this point, we finally have our result:

We can see that this is the shellcode that’s being run in the second stage of the program.

Final Thoughts

While I managed to accomplish my original goal of deobfuscating the first layer of shellcode, there’s still a lot more to analyze here. At some point, it would be a good idea for me to identify the VM instructions I didn’t understand and write a better disassembler. Additionally, I need to look into how the strings constructed by the VM are actually being used, especially as they seem to relate to antivirus software.