Revisiting Emotet

Overview

When I took a course in malware analysis last spring, Emotet was the last sample we analyzed. Because it used some fairly advanced obfuscation techniques, I approached it primarily using dynamic analysis, observing network traffic and seeing what new files were created on the system. However, I was never particularly satisfied with this approach, so I decided to revisit Emotet to try and get a better understanding of what it was really doing.

Specifically, I was looking for the following:

- The sample I studied last spring was a loader that dropped a second DLL from an encrypted resource. Previously, I had handled this by dumping the decrypted resource from memory in a debugger, but I wanted to figure out the decryption method and write a script to decrypt it myself.

- Nearly all calls to library functions were obfuscated. I wanted to see if it was possible to determine what was being called using static analysis alone.

- I knew that Emotet was sending encrypted data to its C2 servers, but when I analyzed it last spring, I was unable to determine the method of encryption or the decryption key. I wanted to intercept and decrypt this traffic.

Additionally, this analysis was my first attempt at using Binary Ninja scripting. Many of the functions in this sample follow similar patterns in how they are obfuscated, so it was relatively straightforward to write scripts to rename certain types of functions automatically. This turned out to be a huge time saver, and I’ll definitely be using it more going forward.

The sample I used in this analysis was obtained from vx-underground, and its SHA-256 hash is 3d2b0b17521278ba782e6c83e3df068de10ba1560d97e987ed4975ef6796f5cb.

Stage 1: The Loader

Looking at the entropy of the given sample, we can immediately see a section with very high entropy:

This appeared to be the same encrypted resource I had encountered when studying Emotet last semester.

Obfuscation Techniques

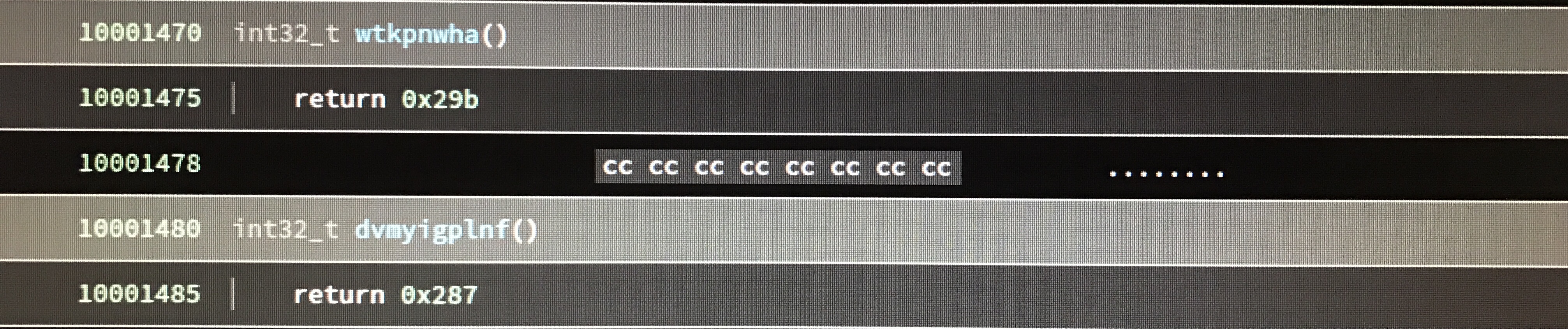

The program obfuscates the use of constant values by defining functions that do nothing except return them:

I wrote a short Binary Ninja plugin to search for functions that do nothing except return a single constant value. When the plugin found one, it automatically renamed the function to show the value it returned.

import binaryninja

from binaryninja.types import Symbol

from binaryninja.enums import SymbolType

# rename the functions that return constants with the values they return

def fix_opaque(view):

for func in view.functions:

for i in func.hlil:

#check if the function immediately returns

if type(func.hlil[0]) == binaryninja.highlevelil.HighLevelILRet:

if(len(func.hlil[0].operands) == 1):

if(type(func.hlil[0].operands[0]) == binaryninja.highlevelil.HighLevelILConst):

#rename the function

name = 'return_' + str(func.hlil[0].operands[0])

s = Symbol(SymbolType.FunctionSymbol, func.start, name)

view.define_user_symbol(s)

binaryninja.plugin.PluginCommand.register("Emotet: Fix Opaque Constants", "rename opaque constants with what they return", fix_opaque)

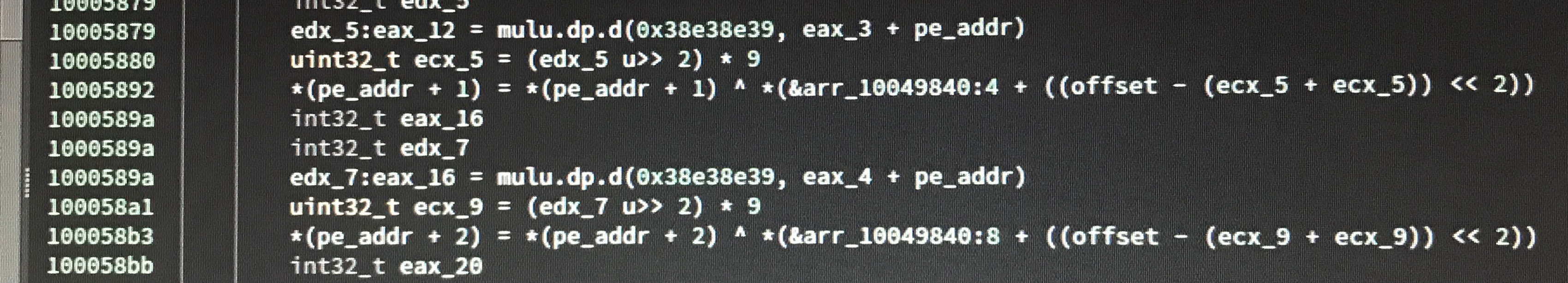

Additionally, some operations are obfuscated by performing unnecessary operations and then reversing them, causing some functions to appear more complicated than they are:

This code appears to be dividing by 9, then immediately multiplying by 9 again.

This code appears to be dividing by 9, then immediately multiplying by 9 again.

Decrypting The Resource

Upon closer inspection, the function responsible for decrypting the encrypted resource was much less complicated than it appeared. Ignoring all of the unnecessary and unused operations, it appeared to be an XOR using a fixed key.

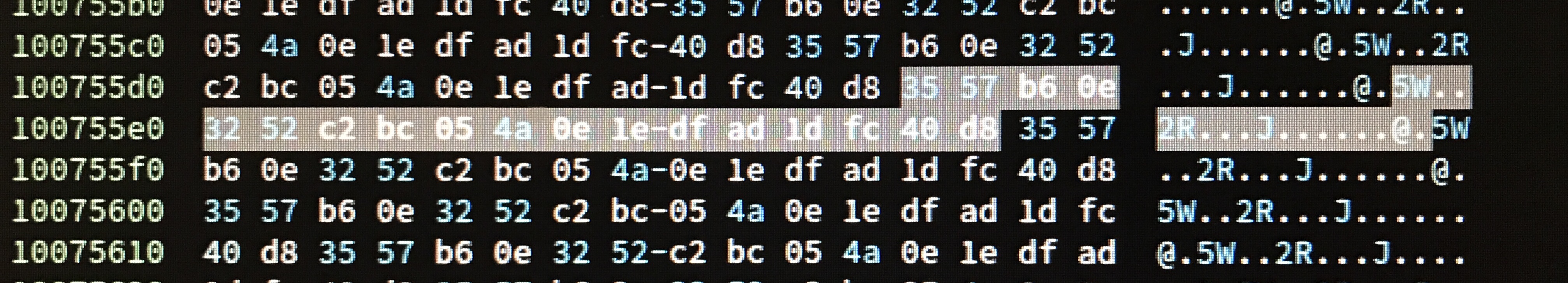

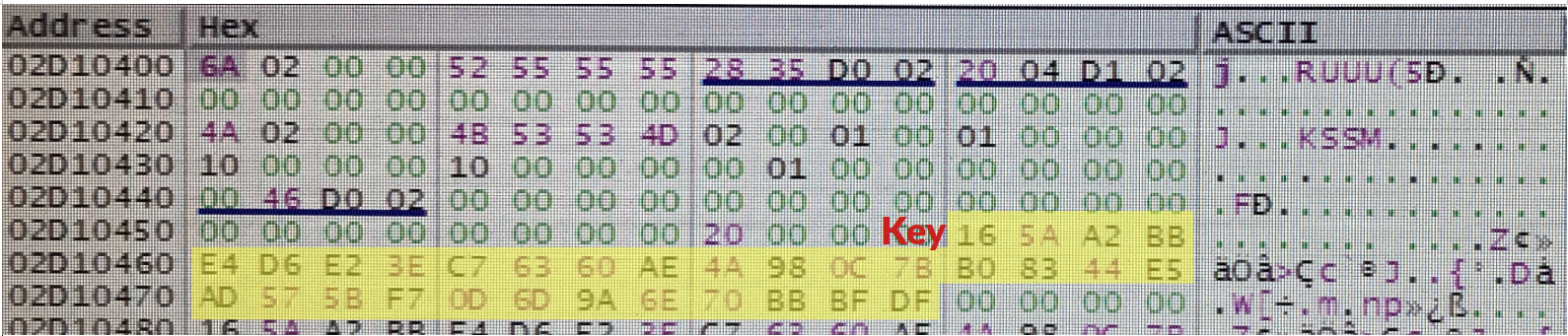

In fact, looking more closely at the resource, we can directly see what the key must be. The sequence of bytes 35 57 b6 0e 32 52 c2 bc 05 4a 0e 1e df ad 1d fc 40 d8 appears over and over in the resource:

We can guess that these correspond to null bytes in the plaintext, meaning that this sequence of bytes is also the XOR key. Performing the XOR, we find that the encrypted resource is a second DLL, as expected.

The original name of this DLL was X.dll. Notably, this was a different version than the one I studied in my malware analysis course - that sample called itself Y.dll. However, the core functionality appeared to be much the same.

Stage 2: The Decrypted DLL

Obfuscation Techniques

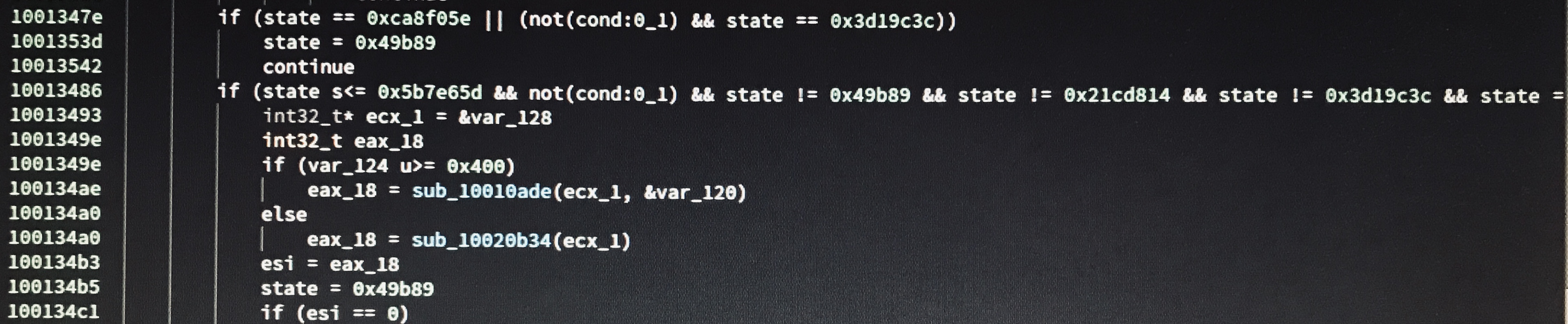

Control Flow

The program uses a long sequence of if/else instructions to obscure the true order in which the code is run. Every time a set of instructions is run, a state variable is updated with a constant value. Then, this value is checked to determine what segment of code should be run next. As the sequence of state variables has no pattern to it, the true control flow of the program is not at all clear.

The sequence of state variables is predetermined, so it should theoretically be possible to reconstruct the control flow. I wasn’t able to do this, but I may come back to it once I’m a little more experienced writing plugins for Binary Ninja.

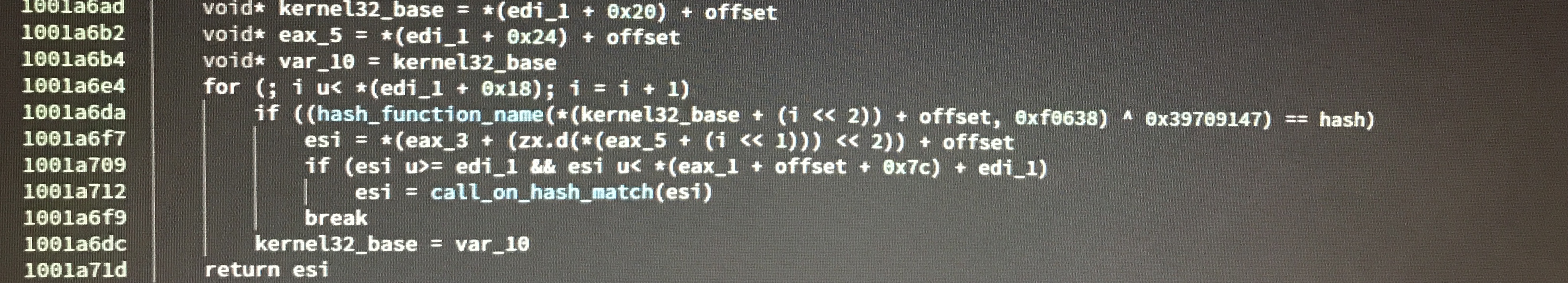

Calling Functions By Hash

System functions are called by passing a hash of the function’s name to the function sub_1001a607, which retrieves the correct function based on the hash. Each of the functions from a given library is hashed until a match is found.

I was able to recreate the hashing function being used:

def get_hash(s):

acc = 0

for c in s:

acc = (ord(c) + (acc << 6) + (acc << (((((0x86270b33 // 0x4b) & 0xff) - 0x58) & 0xff) ^ 0xf9)) - acc) & (2**32 - 1)

return acc ^ 0x39709147

I then obtained lists of the names of all standard Windows functions that the program might call. From there, it was possible to construct a lookup table for each function and its hash.

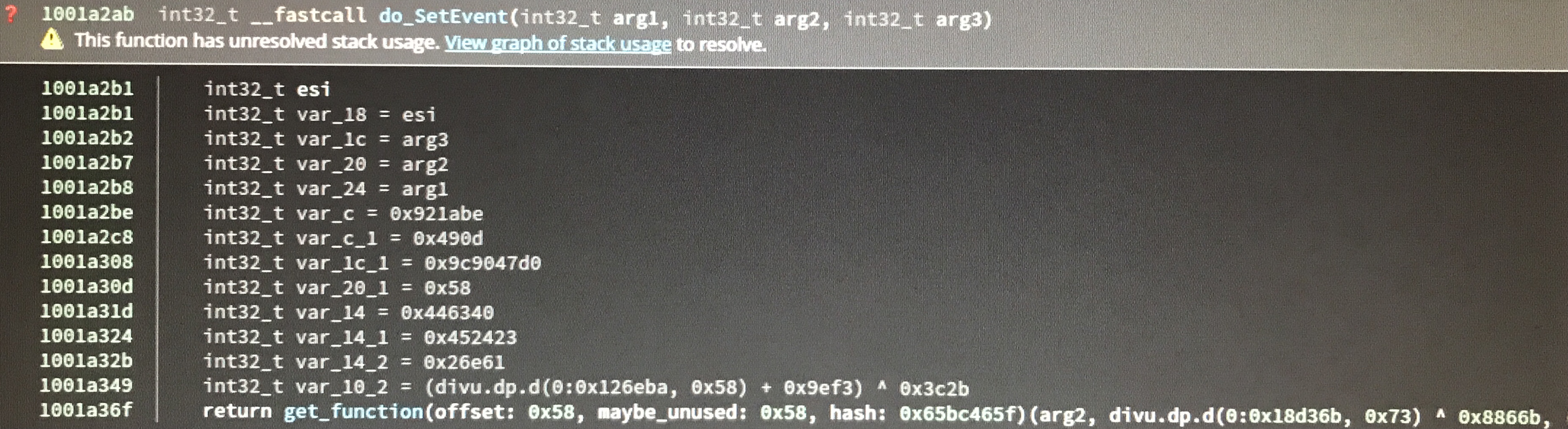

Fortunately, the calls to system functions all followed a predictable format. Every call to a system function was wrapped in a helper function that did nothing but return the result of a system function. Additionally, the value of the hash was hard-coded as an argument, which was enough to determine which system function was being called.

In fact, the pattern was predictable enough that it was possible to search for it and rename each of the helper functions automatically in Binary Ninja:

def get_func_from_hash(view):

func_hash_lookup = {}

# files containing library function names, separated by newlines

for name in ['kernel32_strings.txt','bcrypt_strings.txt','ntdll_strings.txt', 'kernelbase_strings.txt']:

f = open(name).read()

func_names = f.split('\n')

for func in func_names: func_hash_lookup[get_hash(func)] = func

#rename the functions

get_function = view.get_functions_at(0x10002309)[0]

for func in get_function.callers:

#call to get_function is always the last instruction

if type(func.hlil[-1]) == binaryninja.highlevelil.HighLevelILRet:

op = func.hlil[-1].operands[0]

if(type(op) == binaryninja.highlevelil.HighLevelILCall):

try:

#value of hash is the third argument to get_function

args = op.operands[0].params

func_hash = args[2].value.value

try:

name = 'do_' + func_hash_lookup[func_hash]

s = Symbol(SymbolType.FunctionSymbol, func.start, name)

view.define_user_symbol(s)

except:

print("[Emotet] no hash match found for", func_hash)

except:

print("[Emotet] function doesn't match expected format")

At this point, the system functions were fully deobfuscated. This revealed that sub_1000ac95 was making calls to network-related functions such as InternetConnectW and HttpOpenRequestW, and that sub_1000d223 was calling several BCrypt functions. Both of these subroutines seemed worthy of further investigation.

Encryption

Now that I knew BCrypt was being used, I set a breakpoint at BCryptEncrypt. The second argument to BCryptEncrypt is a pointer to the data to be encrypted. It was difficult to tell what everything in this data buffer was, but it did contain the name of the infected computer, so my guess is that it’s all identifying information of some kind.

The first argument to BCryptEncrypt is a BCRYPT_KEY_HANDLE struct corresponding to the encryption key. I eventually noticed a 32-byte value that looked like the key itself. This eventually proved to be an AES key in CBC mode, using an IV of zero.

Network Activity

The program repeatedly attempts to contact its C2 servers at port 80, 443, 7080, or 8080. Each request is of a form similar to the following:

[2022-12-24 11:04:38] [65813] [https_443_tcp 67312] [10.0.0.3:44624] connect

[2022-12-24 11:04:38] [65813] [https_443_tcp 67312] [10.0.0.3:44624] recv: GET /jgmVJehRSbWmVZpyyHuYgnsxkTkjFswtLPOWMdaKBjWknn HTTP/1.1

[2022-12-24 11:04:38] [65813] [https_443_tcp 67312} [10.0.0.3:44624] recv: Cookie: XFGojYhNm=qB51M5FmBrQr2QL0h9q0d+j9/0v0yL31buQC3c13xyhOhwig7oSz5qF2J1IproW5k6uhWeKLV0vfQp6DL+d8taRstSvV7syWiYYQ7b0fEv4ka+UYR4Lr4CC9U/UJsYcElg6w1lp9hqLa3YZ1CGybtymAf+RMMC6rGZTrBcRhRHubbqHJw3T3rJ62/DZBuav5+cxsp3mu+laqkR3MfPyVx/jlLnZQODV7JOi2bBTGvVy7cewAqg3owVYcIdRnR92DjVRQOQUikQbCkTwlJ+bKnZ038J3FF+CWjeBOOCAY8BQrTGeMGvGucjgrkzWYDwpQ

The base64-encoded data in the Cookie parameter contains the AES-encrypted data discussed earlier. Unfortunately, without knowing what kind of response the C2 server would send back, I wasn’t able to progress further.

Final Thoughts

In the end, I was able to figure out how to do most of the deobfuscation I had wanted to do. Once I discovered the hash function that was being used to call Windows library functions, the sample was much easier to understand. In addition, I’m definitely going to spend more time learning Binary Ninja scripting, as it proved to be extremely helpful for this sample.