Flare-On 11 writeup: 07 - fullspeed

Challenge overview

We are given a binary and a pcap containing what looks like random data. In this type of challenge, this usually means that the pcap contains some kind of custom protocol with encrypted messages, and we have to decrypt the messages to find the flag somewhere inside.

Initial guesses and network setup

Before I even looked at the binary, I looked at the pcap itself to see if I could tell anything about the protocol.

00000000 0a 6c 55 90 73 da 49 75 4e 9a d9 84 6a 72 95 47 .lU.s.Iu N...jr.G

00000010 45 e4 f2 92 12 13 ec cd a4 b1 42 2e 2f dd 64 6f E....... ..B./.do

00000020 c7 e2 83 89 c7 c2 e5 1a 59 1e 01 47 e2 eb e7 ae ........ Y..G....

00000030 26 40 22 da f8 c7 67 6a 1b 27 20 91 7b 82 99 9d &@"...gj .' .{...

00000040 42 cd 18 78 d3 1b c5 7b 6d b1 7b 97 05 c7 ff 24 B..x...{ m.{....$

00000050 04 cb bf 13 cb db 8c 09 66 21 63 40 45 29 39 22 ........ f!c@E)9"

00000000 a0 d2 eb a8 17 e3 8b 03 cd 06 32 27 bd 32 e3 53 ........ ..2'.2.S

00000010 88 08 18 89 3a b0 23 78 d7 db 3c 71 c5 c7 25 c6 ....:.#x ..<q..%.

00000020 bb a0 93 4b 5d 5e 2d 3c a6 fa 89 ff bb 37 4c 31 ...K]^-< .....7L1

00000030 96 a3 5e af 2a 5e 0b 43 00 21 de 36 1a a5 8f 80 ..^.*^.C .!.6....

00000040 15 98 1f fd 0d 98 24 b5 0a f2 3b 5c cf 16 fa 4e ......$. ..;\...N

00000050 32 34 83 60 2d 07 54 53 4d 2e 7a 8a af 81 74 dc 24.`-.TS M.z...t.

00000060 f2 72 d5 4c 31 86 0f .r.L1..

00000060 3f bd 43 da 3e e3 25 ?.C.>.%

00000067 86 df d7 ...

00000067 c5 0c ea 1c 4a a0 64 c3 5a 7f 6e 3a b0 25 84 41 ....J.d. Z.n:.%.A

00000077 ac 15 85 c3 62 56 de a8 3c ac 93 00 7a 0c 3a 29 ....bV.. <...z.:)

00000087 86 4f 8e 28 5f fa 79 c8 eb 43 97 6d 5b 58 7f 8f .O.(_.y. .C.m[X..

00000097 35 e6 99 54 71 16 5..Tq.

0000006A fc b1 d2 cd bb a9 79 c9 89 99 8c ......y. ...

[...]

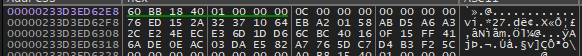

Notice that there are two large blocks of data sent at the start of the communication, followed by many exchanges of variable-length data. Communication over a network often consists of a key exchange followed by messages encrypted by a symmetric cipher derived from a shared secret, and this communication appeared to fit that pattern. This means that to solve the challenge, we have to 1) determine the asymmetric algorithm used in the key exchange, 2) determine which symmetric cipher is being used and how the symmetric key is derived from the shared secret obtained through the key exchange, and 3) find a weakness in either the key exchange algorithm or the symmetric cipher that allows us to decrypt the communications and get the flag.

Before I really got started with the reversing, I set up a simple server to receive network communications from the malware. I used a second VM running REMnux on the same internal network as my analysis VM, configured my analysis VM to use it as a gateway, and used accept-all-ips to ensure that it intercepted all traffic.

By intercepting socket-related system calls I found that the challenge binary did the following:

- Sent two seemingly randomly generated sequences of 0x30 bytes each. This was presumably the challenge binary’s public key.

- Received two sequences of 0x30 bytes, presumably the server’s public key. I didn’t know the format of the key yet, so I couldn’t generate my own, but echoing the challenge binary’s key back to it seemed to pass whatever validation checks it was doing.

- Received more data indefinitely, probably waiting for an encrypted command.

Based on this, I wrote a script to act as a simple server:

import socket

HOST = '0.0.0.0'

PORT = 31337

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

data1 = conn.recv(0x30)

data2 = conn.recv(0x30)

print(f"got data: {data1.hex()} {data2.hex()}")

conn.sendall(data1)

print("sent data1")

conn.sendall(data2)

print("sent data2")

conn.send(b'a'*0x100)

With the server running, the key exchange was able to run to completion, so it was time to start reversing it.

Part 1: .NET AOT reversing

The main difficulty in reversing this binary is that it’s an “ahead of time” (AOT) compiled .NET application. Normally, a .NET binary would contain instructions in the form of IL bytecode that can be decompiled by tools like dnSpy, but it’s also possible to compile the bytecode to native code in advance. This is of course much more difficult to decompile, and the experience of reversing a .NET AOT binary is more like reversing C++ than a typical .NET binary.

The hydrated section

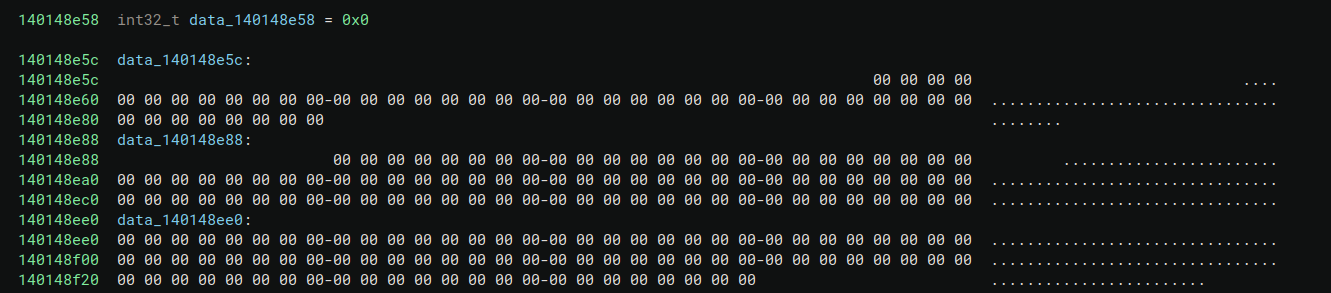

I started off by looking for references to interesting strings, but none of the strings in the binary appeared to be referenced by anything. A closer look revealed that the binary was full of pointers to ununitialized memory in the hydrated section:

From this writeup, I found out that .NET AOT binaries store class structures, including strings, in a compressed or “dehydrated” form as a way of saving space. These structures are then unpacked at runtime. Luckily for us, these structures are unpacked all at once at the start of program execution, so we can easily dump the entire hydrated section from memory. At that point, we can load the new hydrated section into memory in the decompiler.

Binary Ninja gives us the option to load any file at any virtual address (Analysis > Load File at Address...), but unfortunately, strings in the new section don’t appear in Binary Ninja’s Strings view. I worked around this by patching the PE file itself. I appended the dumped hydrated section to the end of the PE file, then edited the sections in PE-bear so that the data at the physical address of the patch was loaded at the virtual address of the hydrated section.

Recovering structures

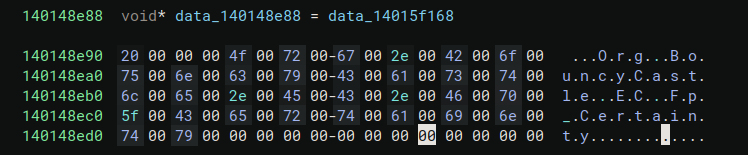

Looking at the hydrated section, I found that every string was stored as a pointer and an integer, followed by the string itself.

It wasn’t hard to guess that the structure of the strings was something like this:

struct DotNetString

{

void* vtable;

uint32_t len;

wchar_t string[len];

};

Unfortunately, this meant that Binary Ninja didn’t display the contents of the strings in the HLIL view - the strings were simply displayed as a pointer to the method table of the String class. I worked around this with a hacky plugin that renamed string structures with the first few characters of the string contents.

def build_dotnet_string(baseaddr):

dn_var = bv.define_user_data_var(addr=baseaddr, var_type=bv.types['DotNetString'])

a = dn_var.value['vtable']

l = dn_var.value['len']

string_var = bv.define_user_data_var(addr=baseaddr+0xc, var_type=Type.array(type=bv.types['WCHAR'], count=l))

dn_var.name = string_var.value.replace(' ', '_')[0:0x20]

There were also a few error logging and exeception handling functions that were called frequently with string arguments, so I searched for cross-references to those functions and renamed any strings that were passed to those functions.

def find_strings(starting_point, which_args):

func = bv.get_functions_at(starting_point)[0]

for site in func.caller_sites:

for arg in which_args:

baseaddr = site.hlil.operands[1][arg].value.value

build_dotnet_string(baseaddr)

print(f"Built string at {hex(baseaddr)}")

Even with the strings identified, reversing the binary was still pretty difficult because most functions were called indirectly through method tables. I used Washi’s Ghidra plugins for AOT binaries as a reference for how these method tables were structured. The tables start with the following header:

struct MethodTable

{

uint32_t flags;

int32_t base_size;

void* addr;

int16_t slot_count;

int16_t interface_count;

uint32_t hash_code;

};

The most important field for us is slot_count, which stores the number of function pointers that appear directly after the method table header. Once we know slot_count, we can define a table of all methods associated with a particular class, and we can identify indirect calls to these methods every time the class is used. This is an example of a decompiled method table struct and its associated function slots:

struct MethodTable EC_FieldElement =

{

uint32_t flags = 0x50200000

int32_t base_size = 0x28

void* addr = 0x14015b7d0

int16_t slot_count = 0x19

int16_t interface_count = 0x0

uint32_t hash_code = 0x6d50bb04

}

struct field_element_functions EC_FieldElement_slots =

{

void* func01 = sub_140075c60

void* func02 = sub_140076590

void* func03 = sub_140076600

void* func04 = sub_140075df0

void* func05 = sub_140075e00

void* func06 = sub_140075e10

void* func07 = sub_140075e90

void* func08 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_FpFieldElement__Multiply

void* func09 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_FpFieldElement__Divide

void* func0a = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_FpFieldElement__Negate

void* func0b = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_FpFieldElement__Square

void* func0c = sub_140076210

void* func0d = sub_140075bb0

void* func0e = sub_140075bd0

void* func0f = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_ECFieldElement__get_IsZero

void* func10 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_FpFieldElement__MultiplyMinusProduct

void* func11 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_ECFieldElement__Equals_0

void* func12 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_ECFieldElement__GetEncodedLength

void* func13 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_ECFieldElement__EncodeTo

void* func14 = sub_140076280

void* func15 = sub_1400762d0

void* func16 = BouncyCastle_Cryptography_Org_BouncyCastle_Math_EC_FpFieldElement__ModMult

void* func17 = sub_140076320

void* func18 = sub_140076560

}

If we can identify even one function in this table, either by using signatures or by finding references within the function to meaningful strings, we can identify the class it’s associated with. In this example, several functions have been identified by their signature as belonging to the EC_ECFieldElement class, so we can use cross-references to this class to find code that’s relevant to elliptic curve cryptography.

Creating signatures

By default, Binary Ninja doesn’t have any signatures associated with .NET AOT. However, we can use the Signature Matcher tool to create signatures for any library we want. This writeup by HarfangLab provides a pretty detailed guide on how to compile a .NET AOT binary containing the most common system functions you’d want to create signatures for. They are also kind enough to provide us with the source code that they used to compile this binary.

I used .NET 8 to compile the signature binary, as the challenge binary contained the string .NET 8.0. I also added in some functions from the unit tests of BouncyCastle related to ECC cryptography and ChaCha20, since it was clear from the strings in the challenge binary that these algorithms were being used. Other than that, I followed the HarfangLab writeup exactly. This resulted in a few hundred functions being identified, including many of the functions that were most relevant to the cryptography.

Part 2: Finding the algorithm parameters

Knowing that ECC was being used, I started looking for the elliptic curve parameters. I would need to find the curve parameters a and b, the prime modulus p, and the generator point G. (For an explanation of what each of these terms are, see my previous writeup on the subject.)

Integers

One of the more annoying things about reversing crypto libraries is that a lot of them use their own custom structures to represent big integers. To find the curve parameters, we first need to figure out how the integer values associated with those parameters are stored and how arithmetic is performed on them. In this case, big integers are stored as an array of 32-bit integers:

struct BigInteger

{

void* method_table;

uint32_t num_qwords;

uint32_t qwords[num_qwords];

}

Each 32-bit integer in the array is little-endian, but the values in the array are stored in big-endian order. This means that the array of bytes representing the value of the BigInteger is neither big-endian nor little-endian, which is something that really tripped me up initially.

ECFieldElement

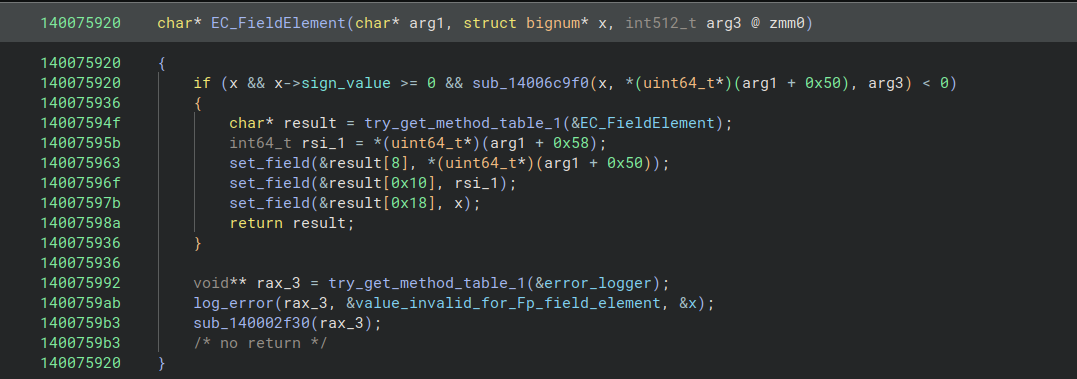

Looking at BouncyCastle’s ECC code, I found that coordinates were members of the ECFieldElement class. An ECFieldElement is an integer modulo the curve prime p, and the class defines methods for performing various arithmetic operations modulo p.

To determine p, I would need to find the offset of the modulus in the ECFieldElement structure. I searched for functions that I thought might take an ECFieldElement as an argument, then compared those to the methods in the BouncyCastle source code. At this point in the process, I hadn’t yet figured out how to generate function signatures, so instead I tried to match the source code with the decompilation by looking for strings. One such string was the string value invalid for Fp field element (FpFieldElement is the base class that ECFieldElement inherits from). I didn’t see this string anywhere in the C# source code, but Googling the string gave me a result in the Java implementation of BouncyCastle:

public ECFieldElement fromBigInteger(BigInteger x)

{

if (x == null || x.signum() < 0 || x.compareTo(q) >= 0)

{

throw new IllegalArgumentException("x value invalid for Fp field element");

}

return new ECFieldElement.Fp(this.q, this.r, x);

}

Compare this with the decompiled function containing the same error string:

If we assume the first argument is an ECFieldElement, it’s clear that sub_14006c9f0(x, *(uint64_t*)(arg1 + 0x50), arg3) corresponds to x.compareTo(q), meaning that the modulus q is at offset 0x50. Setting a debugger breakpoint on this function, we can check this offset to obtain the curve prime p, which in this case turns out to be:

p = 0xc90102faa48f18b5eac1f76bb40a1b9fb0d841712bbe3e5576a7a56976c2baeca47809765283aa078583e1e65172a3fd

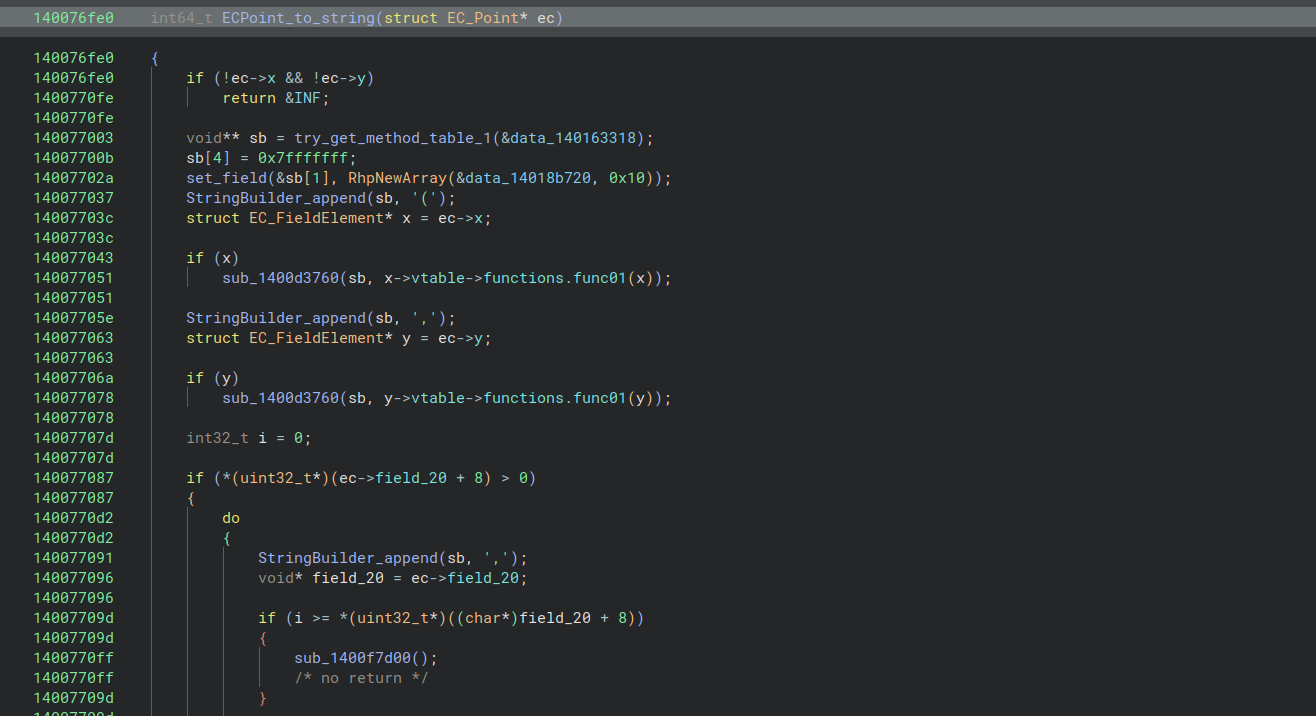

ECPoint

Points on the curve are represented as an ECPoint, which contains pointers to ECFieldElement structures representing the coordinates x and y. In this case, the ToString function was a good one to search for in the decompiled code, as it accesses both coordinates and contains the searchable string “INF”. This told me that x was stored at offset 0x10 and y was stored at offset 0x18.

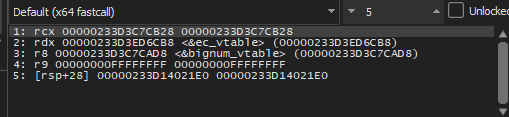

From there, I looked for functions that might have to do with multiplication of an ECPoint by a scalar. I’ll admit, I wasn’t very systematic about how I looked for this function, and I eventually found it mostly through luck and a lot of single stepping in x64dbg. However, one thing that helped a lot was adding labels in x64dbg to the vtables of classes I’d identified, which made function arguments a lot more obvious. When I saw a function that took an ECPoint and a big integer as arguments and then returned another ECPoint, I knew it was a likely candidate for the multiplication function.

One of the first things that happens in an elliptic curve key exchange is the calculation of the public key from the private key, so I looked for the first call to the multiplication function. The point used in the multiplication would be the curve’s generator G, and the scalar would be the private key. I obtained the following value for the generator:

gx = 0x087b5fe3ae6dcfb0e074b40f6208c8f6de4f4f0679d6933796d3b9bd659704fb85452f041fff14cf0e9aa7e45544f9d8

gy = 0x127425c1d330ed537663e87459eaa1b1b53edfe305f6a79b184b3180033aab190eb9aa003e02e9dbf6d593c5e3b08182

The scalar used in the multiplication was a 16-byte value that changed each time. Looking more carefully, I found that the value was being generated by BCryptGenRandom, confirming that it was likely the private key.

ECCurve

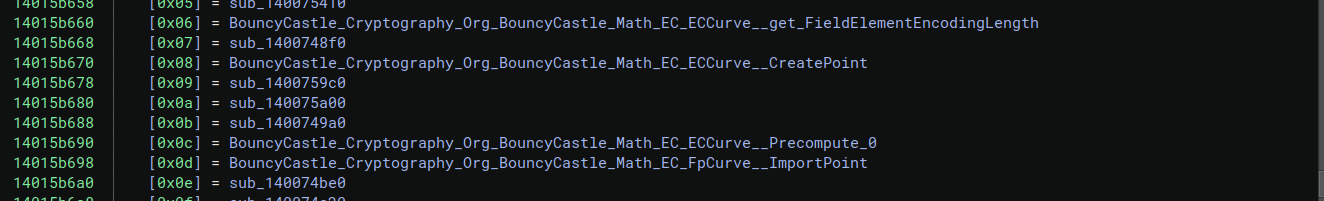

To find the curve parameters a and b, I looked at BouncyCastle’s ECCurve class. By this point I’d figured out how to generate function signatures for the BouncyCastle functions, so the ECCurve vtable was easy to find using the signatures I’d generated.

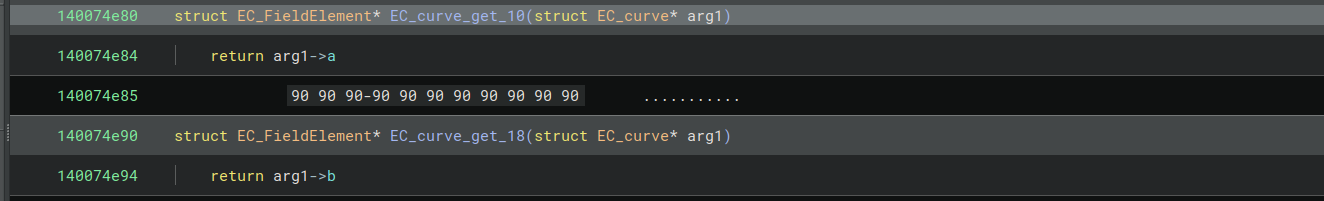

None of the functions identified in the signatures helped me find a and b, but now that I knew which functions in the decompilation were ECCurve methods, I could set debugger breakpoints on whichever ones looked interesting. I eventually saw two getter functions being called that returned ECFieldElements.

These seemed like possible candidates for a and b. Since I already had the generator point, it was easy to check which one was a and which one was b by testing whether the generator point satisfied the curve equation y**2 = x**3 + ax + b. I obtained the following values:

a = 0xa079db08ea2470350c182487b50f7707dd46a58a1d160ff79297dcc9bfad6cfc96a81c4a97564118a40331fe0fc1327f

b = 0x9f939c02a7bd7fc263a4cce416f4c575f28d0c1315c4f0c282fca6709a5f9f7f9c251c9eede9eb1baa31602167fa5380

The symmetric key derivation

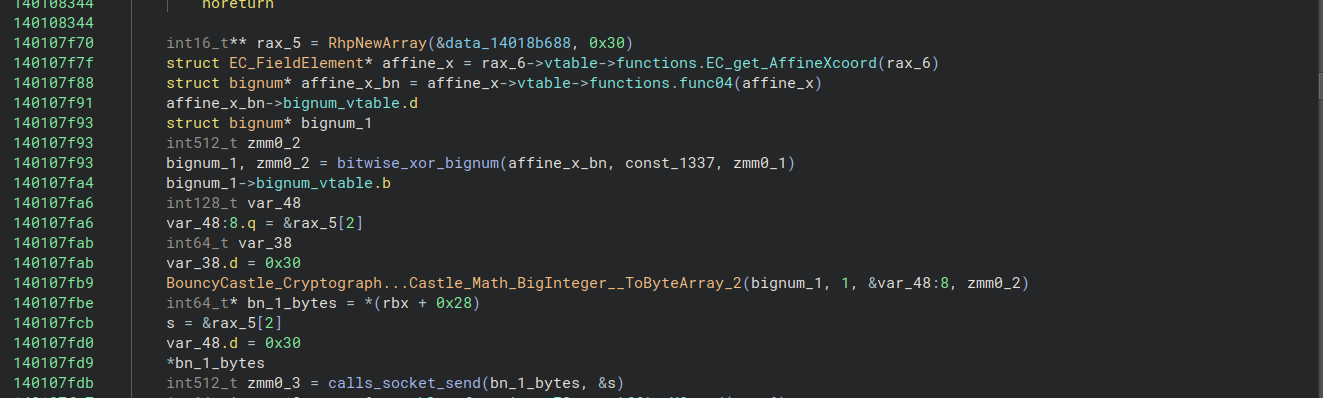

By this point I’d figured out that the main function responsible for the network communication was located at 0x140107ea0. This function calculated the public key, XORed the x- and y-coordinates with the constant 0x1337, sent them over the network, and waited for the server to send its own public key back.

Whatever happened immediately after this key exchange had to be the derivation of the shared secret. I found that the X-coordinate of the public key was being passed to a function that my signature matching had cryptically identified as System_Security_Cryptography_System_Security_Cryptography_CngKey__Import_3. After following several nested function calls, I found that it was calling a function called System_Security_Cryptography_System_Security_Cryptography_SHA512__TryHashData, which is much more helpful.

This meant that the symmetric key was derived from only the X-coordinate of the shared secret, and that the SHA512 hash function was being used to derive the key. Immediately after the SHA512 hash was generated, I saw a call to the constructor for BouncyCastle’s Salsa20Engine that passed in the first 32 bytes of the hash as the key and the next 8 bytes as the nonce. (The Salsa20Engine in BouncyCastle is used for both Salsa20 and ChaCha20, so once I figured out the key I just tried both. It turned out to be ChaCha20.)

Part 3: Breaking the cryptography

Now that I’d recovered all the parameters of the curve, it was time to look for a weakness in the encryption. The only unusual thing about this ECC implementation is that it’s using a custom curve, so the problem likely had something to do with the curve parameters.

My first step was to check whether the generator G was of a small order. This would mean that there would be a small number of distinct possibilities for the private key, which would have allowed us to bruteforce it (see this writeup for an example of a previous challenge with this vulnerability). Unfortunately, it wasn’t going to be that easy:

sage: G.order()

30937339651019945892244794266256713890440922455872051984762505561763526780311616863989511376879697740787911484829297

One thing that stood out, however, was that the order of G was composite. The standard curves used in elliptic curve cryptography all have prime order. Moreover, all but one of the prime factors was very small:

sage: sympy.factorint(order)

{57301: 1,

35809: 1,

56369: 1,

46027: 1,

65063: 1,

113111: 1,

111659: 1,

7072010737074051173701300310820071551428959987622994965153676442076542799542912293: 1}

In order to get an idea of what to do next, I researched past CTF challenges involving custom elliptic curves I eventually found a writeup of another challenge that involved a curve of composite order, which uses the Pohlig-Hellman algorithm to calculate a private key k from the public key point k * G.

The algorithm takes advantage of the fact that if the order of G has a small factor, then it is possible to calculate k modulo that small factor. Given the prime factorization p_1 * ... * p_n of the order of G, if we calculate k mod p_1, …, k mod p_n, then we can use the Chinese Remainder Theorem to calculate k mod (p_1 * ... * p_n) = k mod G.

F = GF(p)

E = EllipticCurve(F, [a, b])

G = E(gx, gy)

order = G.order()

primes = [57301, 35809, 56369, 46027, 65063, 113111, 111659]

dlogs = []

sG = E(x_send, y_send)

for fac in primes:

t = int(order) // int(fac)

dlog = (t*G).discrete_log(t*sG)

dlogs += [dlog]

secret = crt(dlogs, primes)

A more detailed explanation of the attack is available here.

If every prime factor of order was small, we’d already be done. However, the order has one very large prime factor (let’s call it fac), and it would take far too long to solve the discrete log problem modulo this prime. The best we can do is calculate the private key k modulo order / fac. To obtain the value of k from this, we’d also have to know the value of the quotient q = k / (order / fac).

Luckily, there’s another vulnerability we can take advantage of to work around this: the private key is too short. Ordinarily, a private ECC key would have the same bit length as the points on the curve (in this case, 384), but k is only 128 bits, i.e., k < 2**129. Thus q < 2**129 / (order / fac) = 155571. We can easily test every possible value of q within minutes by checking whether it produces the right public key:

secret_mod = 3914004671535485983675163411331184

prod = 4374617177662805965808447230529629

for i in range(155571):

C = (secret_mod + i*prod) * G

if(int(C[0]) == x_send):

print('Found shared secret', secret_mod + i*prod)

break

When I tried this on the sender’s public key from the pcap, the script spit out the private key 168606034648973740214207039875253762473. Exchanging this with the receiver’s public key, we obtain the shared secret:

x = 0x3c54f90f4d2cc9c0b62df2866c2b4f0c5afae8136d2a1e76d2694999624325f5609c50b4677efa21a37664b50cec92c0

y = 0x2793143a038955091171acdcb93bb5b369980f1655c6edcdf5476ed12b5f08465637e6536dd63346aabaf7efb64be82

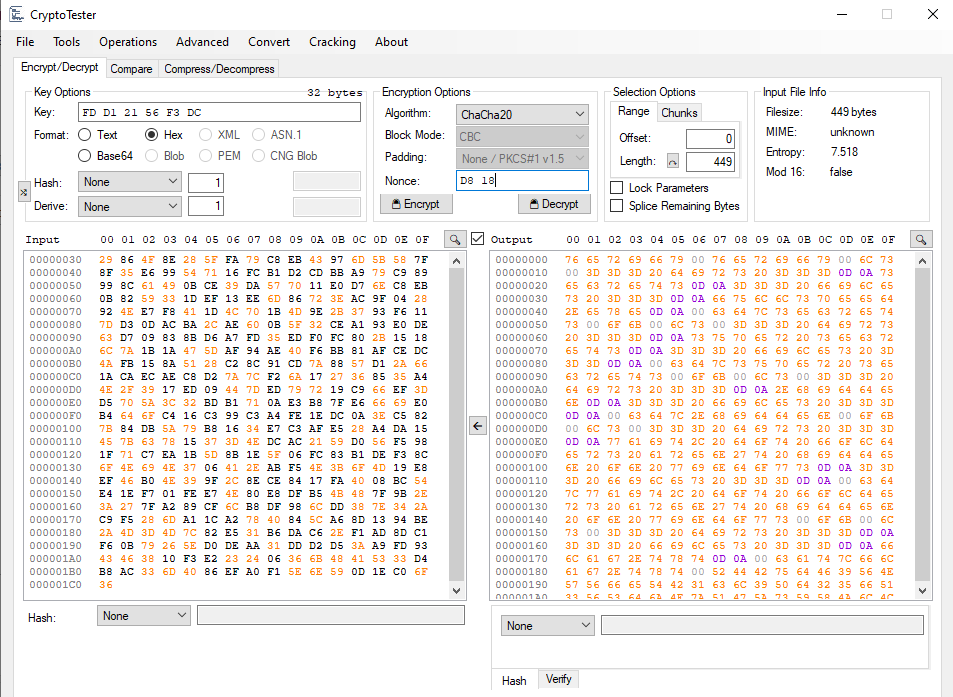

Taking the SHA512 hash of the X-coordinate, we obtain the ChaCha20 key and nonce:

key = B4 8F 8F A4 C8 56 D4 96 AC DE CD 16 D9 C9 4C C6 B0 1A A1 C0 06 5B 02 3B E9 7A FD D1 21 56 F3 DC`

nonce = 3F D4 80 97 84 85 D8 18

Using CryptoTester to do the ChaCha20 decryption, I saw that the result was an ASCII string.

The result was a communication between the client and the server in which the client reads flag.txt from the server’s filesystem:

verify verify ls === dirs ===

secrets

=== files ===

fullspeed.exe

cd|secrets ok ls === dirs ===

super secrets

=== files ===

cd|super secrets ok ls === dirs ===

.hidden

=== files ===

cd|.hidden ok ls === dirs ===

wait, dot folders aren't hidden on windows

=== files ===

cd|wait, dot folders aren't hidden on windows ok ls === dirs ===

=== files ===

flag.txt

cat|flag.txt RDBudF9VNWVfeTB1cl9Pd25fQ3VSdjNzQGZsYXJlLW9uLmNvbQ== exit

Decoding the base64, this gets us the flag: D0nt_U5e_y0ur_Own_CuRv3s@flare-on.com